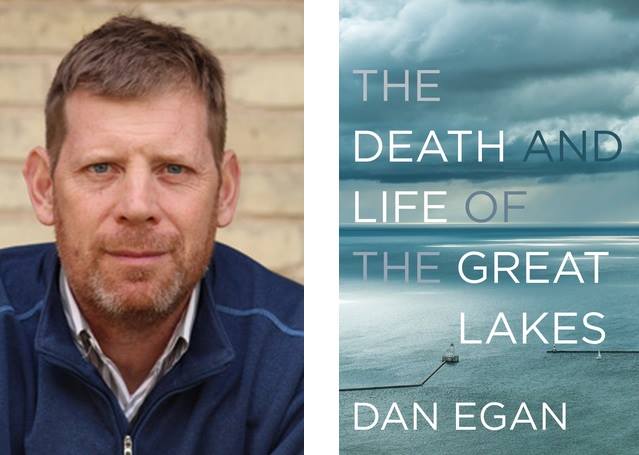

Dan Egan’s The Death and Life of the Great Lakes invites the reader to reimagine the Lakes as substance and space in some distinct and disturbing ways. As watershed and geography, the Lakes have undergone a profound shift over the last half century-plus. Here, Egan offers a clear eco-history of those shifts and prompts a means of reimagining the Lakes’ next century of human use.

Egan underlines that, through their history, the Lakes have been relatively isolated—at the head of the St. Lawrence River, protected by Niagara Falls. This position leaves them ecologically fragile, susceptible to relatively sudden shifts in fish and plant populations. Trawling surveys measured Lake Michigan’s biomass in the late 1980’s at around 350 kilotons; by the end of 2015, that same measure did not even reach a single kiloton (124-6). An invading species’ undetected presence can lead to volatile results in the Lakes’ food chain and ecological balance—shifts that are even more pronounced as human geographies evolve and regulatory agencies seek responses to manage the Lakes into the 21st century.

Much like the prairied “river of grass” to the Lakes’ west, Egan encourages the reader to rethink these bodies of sweetwater not as undisturbed ponds, but as a river—one that tips slowly from Superior down through Huron, along the St. Clair River, into Erie, and over the falls into Ontario. Human movement against that long, slow pull of waters is Egan’s story—human activity in the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway and human inactivity in face of those oft unrecognized ecological shifts posed by invasive species and agricultural run-off. To the east, Lake Erie remains vulnerable to the development of toxic algae blooms, spiked by the presence of fertilizers carried by the Maumee River (with concentrations of phosphorous 30 times higher than the larger Detroit River [235]). Globalized trade has brought invading species that have no known predator in the Lakes; Egan writes, “Call it the Caspianization of the Great Lakes” (127). The western Lakes’ underwater geographies have been remapped by the quagga muscles that have proliferated well into the Lakes’ depths, invaders that have sapped the plankton that rest at the base of the Great Lakes’ food chain.

Meanwhile, attempts to manage the Lakes’ problems have been stalled by boundaries between nations and governmental agencies. Costs of ecological changes mount; cities and power companies have poured $1.5 billion over the past 25 years to keep muscles from clogging pipes from the Lakes (147). And as the demands for sweetwater build, the United States drains its aquifers and waits out historic droughts. Even more recent attempts to clarify the geographical relationships here (i.e., the Great Lakes Compact) have prompted legal and legislative quandaries that are in the slow process of being resolved as the next invasive species might be waiting in the bilge tanks of a ship making its way through the Seaway locks.

With the moving waters, is it a question of will? Egan argues, “Like generations of the past, we know the damage we are doing to the lakes, and we know how to begin to stop it; unlike generations of the past, we aren’t doing it” (xviii).